I started making pickled eggs in late summer 2007, as I recall, as “a thing to do” to contribute to a church bazaar’s preserves table. I had never eaten, let alone made, pickled eggs before; it was just an “out of the blue” conviction that had come to mind. The first appearance of my eggs at the church bazaar was in the fall of 2008; I had believed that for the fall 2007 bazaar, I’d begun too late to pick up some confidence in making them in order to present my offerings at that year’s bazaar.

In the process, I learned how to make the pickled eggs, got some practice under my belt, and got a bit of an overview of the process.

Interestingly, the pickling solution I found on the internet, which I continue to use to this day, was key to what I now consider a long standing success. Shortly after having begun my adventures in pickling eggs, I bought a jar of pickled eggs at the store. I found said eggs to be slimy, and the pickling solution sour and too mouth puckering. I ended up giving away the open jar to a family friend who liked them that way better than the recipe I use. Had I bought the pickled eggs at the store first, I doubt I would have ever embarked upon making pickled eggs myself.

I began by buying small eggs, and stuffing as many as I could per mason jar; I soon began buying large eggs, and would pack the mason jars somewhat less tightly. See below in the “Jars and Lids” section for further suggestions on how many eggs to pack per jar size.

Of course, I keep my eyes out for sales on eggs. In the Montreal, Quebec (Canada) area in 2017-2018, a price of $5.50 for three (3) dozen eggs was a good sale price. I will also buy eggs on sale at $1.99 per dozen. (Prices in Canadian dollars.)

I eat my pickled eggs almost daily. I continue to make the eggs for my church’s fall fair, although they typically only end up selling less than half a dozen jars each year. And, I now make large numbers of pickled eggs for a small flea market in which I participate each year. (See further down.)

Making pickled eggs, tips, and experiences:

I have seen various instructions on how to boil eggs, how long to boil them, and how to cool them properly in order to shell them easily and perfectly. I have a view on that: boiling and shelling eggs very largely isn’t about tricks and shortcuts, or such-and-such a special method. It’s simply about boiling them the right amount of time, rapidly cooling them with ice, and a lot of work removing the shells. Yes, some eggs shell more easily than others, and vice versa. I have decided to give up on most theories on why eggs, particularly sometimes whole boxes of eggs, tear easily when shelling them. One must simply immediately and abruptly cool them after boiling, using ice water, and be careful while shelling eggs; fortunately, I seem to have learned over the years how to shell eggs while largely avoiding torn eggs, barring the occasional batch of eggs that tear far more than usual.

What do I do?

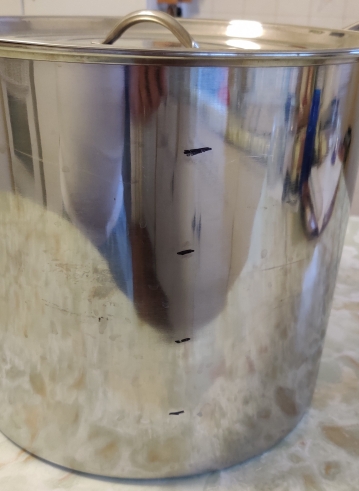

- I boil 18 cold eggs at a time. This number generally works well for me. You might find another number works well for you.

- Fill the pot with cool to cold water to roughly an inch (2.5 cm) above the eggs.

- Bring the pot to a boil.

- Boil for eight (8) minutes.

- Immediately drain the boiling water, and begin running cool to cold water over the eggs.

- Immediately add ice cubes to the pot (keep the water), covering the eggs completely, and begin shelling a few minutes later when much of the ice has melted and the eggs have largely cooled.

Despite my instructions above, I have some recent and long term observations regarding this process:

- When making large batches of pickled eggs, it takes time. I find that there is little way around this, beyond having a helper or outright equal partner, if only because I find that boiling larger numbers of eggs at once makes for more variable cooling of the eggs (quick cooling being needed for easier or at least less difficult shelling), and that beginning the next round of boiling 18 eggs while still shelling already-boiled eggs is perilous, from the perspective of a less than optimal personal ability to manage multiple things at once in the kitchen.

- The ice should be in cubes, not larger pieces of ice. I am blaming a recent experience of a relatively high rate of torn eggs in a batch on the fact that the ice I was using was made in plastic food containers, making ice blocks far larger than typical ice cubes, and the notion that that probably affected the cooling rate of the eggs.

- In my personal experience, a torn egg rate of about one egg per dozen is normal, to be expected, and not to be fretted over. As far as I’m concerned and for pickling purposes, a torn egg is anywhere from a bit more than a dimple until just before it’s completely in several pieces. (Use the eggs which completely break up for snacking while you work, or making egg salad sandwiches later.) Torn eggs will pickle just as well, and are put aside, to be bottled together in my personal consumption jars of pickled eggs, and not to be given away. This is of course purely aesthetic; but at a certain point, were a customer to buying from me, they would (rightly so) ask for a discount on a jar of torn pickled eggs.

Jars and lids:

I pack my jars as per follows: 6 eggs per 500mL mason jar, 9 eggs per 650mL jar (from a favoured brand of spaghetti sauce whose jars look like, and appear to act like mason jars, though according to some sources do not meet mason jar standards), 14 eggs per 1 litre mason jar, 22 eggs per 1.5 litre jar (a commercial jar that is not mason), and 30 eggs per 2 litre jar (“large” commercial pickle jars — yes, I imagine that most people might consider “large” jars more likely to be the 4 litre jars of pickles like you mostly see at restaurants and delicatessens).

The largest sized jar I like to pack are 1.5 litre glass jars. They hold 22 eggs, and this size is now my reference for the largest jar size with which I want to work. 2 litre jars hold 30 eggs and are a bit too big, unless, of course, I am trying to make a clownishly big jar of eggs, which in the past I have wanted to do, and which in the past I have done. I have no intention of ever packing 4 litre jars.

I give away and occasionally sell my eggs (see below), which means that over time, I have to acquire new mason jars of varying sizes. While I obviously reuse my mason jars after I empty them, occasionally come across mason jars in recycling bins, and receive empty mason jars from friends and family for free, I still eventually need to replenish my supply of mason jars.

While I live in the big city where buying new jars by the case is a trivial matter, I normally go to a nearby used-goods store, part of the Goodwill Network. I buy mason jars one to several at a time, depending on what’s available, my needs, and whim. Putting aside any illusions I do indeed have of “reusing and environment”, and fewer illusions of “helping people” (ie. not that the store isn’t helping people, just that doing so isn’t particularly one of my motivations when it comes to purchasing the mason jars or anything else there), I enjoy the convenience of getting them there, not getting a dozen at a time, and not having to pay any sales taxes (which is part of the local provincial and federal governments’ support of social and employment re-insertion programmes). I normally only buy the Bernardin and Golden Harvest branded mason jars of 500mL and 1 litre sizes, while not the older mason jars in Imperial measurements (Canada has been metric since the mid-1970’s), and/or those which often are somewhat to very square — eggs, after all, are round! 🙂 I don’t buy other non-mason formats of jars, nor the 650mL mason jars that come from a commercial spaghetti sauce which is sold in jars which look like, and appear to act like mason jars, though according to some sources do not meet mason jar standards, since I get enough of them from my other cooking projects.

I look for pricing on the individual jars at 50 cents per 500mL mason jar, and 75 cents per 1 litre mason jar, and look for mason jars which (normally) have the old lids and rings on them. (A bit more on reusing lids below.)

I normally buy new lids at a local dollar store chain at 12 for $2, plus taxes, bringing the price per lid to under 19 cents per lid, or about 69 cents per 500mL mason jar, or 94 cents per 1 litre mason jar.

Occasionally, I purchase boxes of 12 lid and ring combinations, but the last time I did so, if I remember correctly, the price would have been to the order of $5.39 plus taxes. This would make the lid-and-ring combination cost just under 52 cents each, for a total of $1.02 per 500mL jar, or $1.27 per 1 litre jar.

The clincher: WalMart sells cases of 12, 1 litre Golden Harvest mason jars, (obviously) with new lids and rings, for $9.49 plus taxes, or just over 91 cents per mason jar. Only compared to the more expensive Bernardin mason jars are the reused 1 litre mason jars I buy more competitive.

So, the purchased reused 1 litre mason jars with a new lid, when I sell them (see below) — hence not counting them as a cost when I use them for my own use, and then use them again when empty — are only competitive cost-wise with new mason jars when I am able to use used rings.

Since I use the 650mL mason jars from the commercial spaghetti sauce I use, their cost is hidden in the price I pay for the spaghetti sauce. Of course, I only buy them on sale. 🙂 Hence, the direct cost per se per such jar is for the lid only, ie. about 19 cents (lid only) or 52 cents (lid and ring).

Lids:

Normally, when I make my eggs, one of the many “either / or” categories that go through my mind is personal consumption vs. the rest, which are potentially destined to be eaten by anyone, be it by sale, gift, or plate of hors d’oeuvres being passed around. I reuse lids for the personal consumption group, but all others receive new lids, mainly on ethical grounds based on the lids normally having been designed for single use. I have generally had excellent results reusing lids, and the only problems I have had with seals were related to some floating spices happening to get caught in the rubber seal, preventing the seal from working correctly at that location.

As for rings, I try to reuse rings as often as possible (and therefore, when buying jars at the used-goods store, trying to get as many as possible with the rings and lids). Normally, I throw away rings with any non-trivial amount of discoloration or oxidation, while reserving those with slight discoloration for my personal consumption, and finally spotless rings for the jars being sold or given away.

A recent experience using a used lid on a commercial jar:

During one of my recent batches of pickled eggs, I had intended to fill my 1,5 litre jar (capacity of 22 eggs) to be a showcase jar during an upcoming flea market at which I was going to sell my eggs, with the expectation that I would have no clue as to whether or not it would sell. During a previous flea market, I had prepared a 2 litre jar containing 30 eggs to act as a showcase jar; it drew the attention of only one person. who ended up not buying it on the advice of his wife. (She figured it would be far too large and would likely end up mostly not consumed; her husband purchased a far smaller jar.)

However, this year’s showcase jar was not to be; the cooking session during which I was to make the jar unfortunately included a higher-than-normal rate of torn eggs, coincidentally 22 eggs above the expected rate of one egg per dozen. Hence, the jar was filled with the 22 most torn eggs, and kept for personal consumption.

I had used a “new to me” lid on the 22 egg jar: The lid came from a commercial jar of mild salsa, the salsa jar’s neck having the same size as the neck of the 1.5 litre jar. It sealed great.

When I opened the jar and ate an egg, I noticed that the flavouring was somewhat different from usual. Good, but a bit different.

The next morning, I noticed the flavouring again, and realized that many of the eggs in the jar would likely taste that way. I began to identify the new flavour, and I realized why it was there.

The reused lid had absorbed and retained some of the spicing from the salsa jar, which then was released in the vinegar in the egg jar. Of course the lid had been properly washed in a dishwasher prior to use, and put in the boiling water immediately before bottling the eggs.

Fortunately, after a few eggs, the salsa spice taste was no longer present. (I am not a fan of salsa nor salsa spice, but the taste transfer was very mild.)

So beware of reusing lids!

The obligatory wash-and-boil-your-jars-and-lids comment section:

When bottling your now-boiled and shelled eggs, and adding your now-boiling pickling solution, it is imperative that the following things be respected:

- All used jars need to be visually inspected for cracks, chips and other defects; the presence of any of these are cause not to use them for canning of any kind;

- All used jars need to be properly washed in advance (lids and rings, too);

- At bottling time, your jars and lids need to be in a boiling water bath. I have found that for pickled eggs, the time it takes to put several in the boiling water bath and then the time to take them out and immediately fill with the eggs and pickling solution, one jar at a time, is sufficient;

- At bottling time, your pickling solution should be kept boiling in between filling the jars;

- At bottling time, I have found that immersing your shelled eggs in a boiling water bath for the time it takes to place them in the bath and then remove them and immediately transfer them to a jar that has just been taken out of its boiling water bath, is sufficient;

- At bottling time, your lids should be taken out of the boiling water bath and immediately placed on the just-filled jar.

In this section, the Hallowe’en Candy Rule applies:

I most recently was selling my pickled eggs at a small flea market in June, 2018. In the months leading up to the flea market I had prepared, over roughly eight cooking sessions spread over three weekends, the following amounts of eggs:

- (roughly) 29 jars of 6 eggs;

- 9 jars of 9 eggs;

- 9 jars of 14 eggs, plus:

- 1 jar of 14 eggs, to keep for myself;

- about 7 jars of 6 torn eggs;

- 1 jar of 12 torn eggs; and,

- 1 jar of 22 torn eggs.

This was based on rough notions of:

- in years past, at the same flea market, I have sold as many as 19 jars of 6 eggs;

- last year, I believed that I could have sold more than the 2 jars of 14 eggs and 4 jars of 9 eggs that I had prepared for the flea market, had I prepared more jars of those sizes;

- prior to the flea market, I unexpectedly sold 4 jars of 6 eggs, then 2 jars of 14 eggs, then 3 jars of 14 eggs, to a contact through work who adored my eggs upon tasting them one day when I randomly decided to bring some to the work site (and therefore I had to scramble to make more of the large format!);

- I would want / need a few jars for use at parties, and giving away in the intervening period and beyond;

- my accepted torn egg rate of one per dozen, which materialized pretty much spot on, except and therefore plus the unexpected extra 22 torn eggs during one cooking session;

- relative unbridled enthusiasm. 🙂

Which leads to the Hallowe’en Candy Rule: Why would I want to go to all that trouble? And what do I do with any leftovers? Well, the Hallowe’en Candy Rule says that you should only give out candy that you would not mind having a large amount of leftover should you have overbought supplies, or should there to be few children who knock on your door for any of a variety of reasons like inclement weather, or a last-minute public scare causing parents to restrict their children’s trick-or-treating, or a change in neighbourhood demographics, or any other reason. In this case, it didn’t matter if I overestimated the number of eggs to make for the flea market: I like my pickled eggs, and any excess would be eaten by me, be brought to parties as hors d’oeuvres, or be given as gifts.

And how did the most recent flea market I participated in turn out?

For selling eggs, until recently, I priced the eggs at 50 cents per egg, except for the jars of six eggs, to which I would add an extra 25 cents to help compensate for the mason jar costs. As of June, 2018, I now charge closer to 57 cents to 58 cents per egg (slightly variable depending on the jar size and rounding to the nearest 25 cents), which incidentally also brings the prices closer to the lower end of the range of prices for pickled eggs at grocery stores.

The previous price of 50 cents per egg was me being modest, and perhaps simplistic. I knew that other artisans were selling 500mL jars of artisan pickled products and jams and jellies at $5.00 and more, depending on the item. But I felt I couldn’t justify that much, and in any case, I had seen jars of 6 pickled eggs at a local discount store for about $3.49. I felt somewhat uncomfortable raising the price on jars of six pickled eggs to $3.25 last year, despite it being on account of recovering some of the jar costs. As of this year, jars were priced at $3.50 per jar of six eggs, $5.25 per jar of 9 eggs, and $8.00 per jar of 14 eggs.

Despite this year’s price adjustments, nobody said boo. The number of sales on some sizes were up from last year despite the price increase. And where it was down, I attributed that without hesitation to foot traffic and variations in salesmanship.

A quick back-of-the-envelope tally of sales income and costs for all the jars of pickled eggs listed above suggest that as a batch, I recouped my investment, and my margin is in the leftover product, including the torn eggs which were never intended to be sold (and weren’t). Leftover amounts of unsold product intended to be sold were to the order of 13 jars of 6 eggs and 4 jars of 9 eggs. As mentioned earlier, the Hallowe’en Candy Rule was not only a guiding factor in the business plan; in the end, it certainly proved to be an integral part of the business plan.

Update: There is a second post on pickled eggs from October, 2018.