As I recall, I began cooking big batches of soup (eight quarts and more) for my church’s after-service social time / coffee hour in early 2013.

On a lark, I had decided one winter Saturday afternoon that it would be a good idea to make soup the following morning during the church service and serve it during the after-service social time / coffee hour. I sought out a recipe on the internet for “big batch vegetable soup”, which sent me to a recipe on the Martha Stewart website for four quarts. The recipe suggested that it was very flexible, so I chose the ingredients I liked, ignored those I didn’t, and doubled the numbers to make eight quarts, the size of a large stainless steel pot I had. The next morning, I bought the requisite ingredients on my way to church, and upon arrival, I just started making the soup in the church kitchen during the service. During coffee hour, it was a modest hit; all of the soup was served, with none left over.

Since then, my vegetable soup recipe, having evolved somewhat from Martha Stewart’s, has become a small yet (I hope an) integral part of what has become a larger occasionally recurring food event.

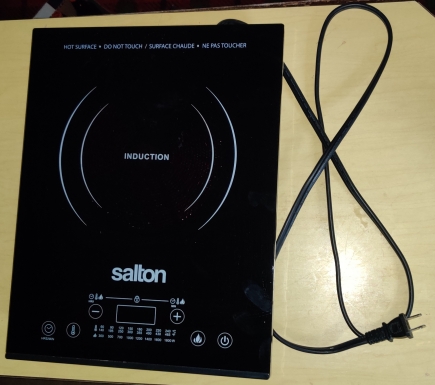

This is in no small part due to a comment I received from a fellow parishioner that Sunday morning in early 2013. By the time she managed to come to my service table, the soup had cooled too much for her liking; this prompted me to invest in an inexpensive portable counter top single burner electric stove. At the least, the theory went, I could cook the soup in the church kitchen, and then upon bringing it out to the hall for serving, I could keep it hot. Since then, however, I have shifted to cooking the soup in the hall where it has been served, avoiding in the process the danger of walking through a hall with a large pot of boiling soup at a time when it starts filling with people.

I have since invested in the following (photos added 20250202):

- a double burner counter top portable stove:

- two more inexpensive single burner electric counter top stoves;

- a somewhat more expensive, single burner induction counter top stove;

- two 50 foot, 12 gauge extension cords, one of which normally does not get used;

- and, I already had an eight quart stainless steel stock pot:

- In addition the pot I had, I bought:

- an eight quart stainless steel pot I found at a steal of a price at a second hand shop:

- a slightly used 16 quart stainless steel stock pot at a steal of a price at a second hand shop;

- a new 20 quart stainless steel pot for a steal of a price at a grocery store.

In a number of ways, portable counter top stoves are central, however indirectly, to the success of the soup I make, despite the relatively large volumes of soup I now occasionally make.

Over time, I have learned how to make large quantities of crowd-pleasing soup while also discovering some of the limits of counter top stoves, as well the upper limits of the environment in which I am using them.

My single burner, traditional coil stoves are rated at 1000 watts each (8.33A @ 120V). My double burner coil stove is rated for a total of 1500 watts (12.5A @ 120V). My single burner induction stove is rated at 1800 watts (15A @ 120V).

In my experience, it is possible to make the following capacities of my vegetable soup (your results may vary according to your soup recipe):

- 1000 watt single burners:

I find that these units may be used for making eight quarts of soup in a two hour period, and 16 quarts if you have at least three hours to make it. (As a second burner, it also allows for the frying up of vegetables that are later added to the soup pot, although depending on your site conditions, you may not be able to operate both burners simultaneously at maximum capacity.)

- 1500 watt, double burners:

I am able to make two eight quart pots of soup in a two hour to two and a half hour period.

- 1800 watt, single burner induction stove:

Particularly ideal for making eight quarts of soup in less than two hours, and it will handily make 16 quarts of soup in a couple of hours. It will also bring 20 quarts of soup to a boil in just over two hours.

Planning, preparation, and logistics of “mobile cooking” for a crowd

This post is not on how to cook a full, multi-course meal or buffet for a large crowd; rather, it is about just a relatively small part of it. As described later and despite describing the portable stoves as being central to the cooking of the soup which is one of the two subjects of this post, attempting to cook a full, multi-course meal or buffet for a large crowd with consumer grade portable cookware, and in environments not set up for such cookery, is impractical at best; to do so would require planning and menu design far beyond the perview of this post.

Setting up and preparation:

Often when travelling to cook for a crowd, one is doing so in an environment that is unfamiliar, and depending on the circumstances (such as the type of hall in which I make soup for a crowd), is not set up for doing so.

From a cooking perspective, this means that I normally do more than simply collect the soup ingredients and throw them into a pot, hoping that tasty soup will come out a couple of hours later. Often, this means now that while cooking the soup takes place in the church hall, I prepare the ingredients in advance at home, typically the day before. Fresh vegetables are cleaned, chopped, and placed in containers for transport. Usually, they are mixed together, and even the olive oil is added and mixed in. Frozen vegetables are taken out of the freezer the day before in order to defrost them at least somewhat, so as to reduce the amount of time required to defrost them during cooking. I also transport all the fresh food in a cooler.

Equipment-wise, I bring most of what I need for the cooking part. (Fortunately, my church has tables, tablecloths, chairs, dishes, a commercial dishwasher, and the like.) Of course I bring the portable stoves and my pots, however I also bring my own cast iron fry pans and cooking utensils, such as spatula, ladle, and can opener. I even bring my own towels for cleaning up my area, which of course I launder myself.

Real life challenges to using portable stoves in areas not designed for cooking

I once agreed to making my vegetable soup for my church for the Fall Fair Luncheon, at which the soup would be the main dish. This was in contrast to my normally serving it informally in a mug as I usually do during Sunday coffee hour — sometimes on its own, sometimes as part of a modest luncheon — after the church service. This meant that I attempted to make a total of 44 quarts of my vegetable soup simultaneously in the same church hall. I came upon a reality of what I can only presume is a common condition of many halls not expressly designed (or recently upgraded) for high electrical demands, such as cooking for the very crowds they were designed to welcome. “That’s why there’s a kitchen, silly!”

I ended up learning definitively that the hall in which I was cooking the soup had only one electrical circuit, with what I was told (and which I later confirmed) was a 20 amp fuse. A quick addition in my head indicated that at its peak when I was trying to bring all 44 quarts of soup to a boil simultaneously, I was trying to consume between 29.6 to 31.7 amps on what proved to be a single 120V / 20A circuit!

(Note: I live in Canada, where the mains voltage is 120 volts, and unless specifically designed otherwise, circuits and circuit breakers — and in the still common situations where fuses are still used — are generally designed and set for 15 amp loads. I can only assume — hope and pray — that the 20 amp fuse in place upon which I normally rely is there legitimately.)

It also led to what I consider to be an unfortunate conclusion, in the context of my desire to publicly (as opposed to hidden away in the kitchen) make my soup for a large crowd: The electrical outlets in many halls, designed and built decades ago, are often served by a single electrical circuit. Hall and home builders simply never envisioned nor intended for cooking, which often requires a large amount of electricity, to occur outside of a kitchen; at most, they may have assumed that someone might plug in the equivalent of a plate warmer, possibly two, to keep a casserole or two warm.

This led to my realizing that making my vegetable soup for the church had its limits. With some patience, I could still make my soup in relatively “small” quantities — usually up to 16 quarts at a time, and perhaps if I reduced the heat a bit at certain times, perhaps fry up the vegetables at the same time. However, the fuses blowing a few times confirmed that large quantities of soup — and more generally, large scale cooking — could not be cooked simultaneously in an area not set up for the loads required for cooking. This means that despite the fact that a “large hall” may have many outlets, unless the hall was designed or since upgraded for heavy electrical loads, there is a good chance that the many outlets are in fact all on a single electrical circuit.

Although I purchased all of my portable stoves for cooking in non-traditional areas, as I’ve learned, their value for cooking in certain circumstances is limited to actual cooking of relatively small amounts of food — as in, depending on which stoves are chosen for use, that which may be cooked on one or two portable stoves at a time — and only keeping warm to hot larger quantities of food that have already been heated up, only then using more of my portable stoves at once.

Which leads me to the following conclusion: Portable cookware are very useful tools for the traveling cook, but one must not have have illusions of “feeding the multitude” based solely on these tools.

Captain Obvious Update Comment: Putting aside (possibly sardonic) suggestions of “use the kitchen, silly”, it has occurred to me that some may say “well use a portable gas stove to avoid the problem with electrical limits”. To me, the obvious issue becomes one of ventilation being required to avoid the buildup of combustion gases, particularly carbon monoxide. Some may well bring a fan to prop in a nearby open window in order to assure extraction; this would require such a window can be conveniently located. Yes, I have an opinion on that subject, too, to the order of old windows that were never designed to be opened, or which have been long since painted shut. 🙂